CONFLICT FINANCE

Conflict actors must sustain access to financing to maintain their operations. Additionally, the potential for outsiders to profit from conflict can also grow to become a key driver of the conflict itself.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The IMF has usefully set out the landscape of conflict finance here. The details are out of date.

https://c4ads.org/

C4ADS is a nonprofit organization with a mission to defeat the illicit networks that threaten global peace and security.

C4ADS provides valuable current information on conflict finance.

C4ADS identifies the mechanisms that elites use to profit from conflict, revealing the financial interests of conflict actors, and exposing the illicit markets that create or sustain conflict. By illuminating the economic drivers of conflict, we provide actionable information for decisionmakers to build new pathways to peace.

As an example a publication by Jack Margolin and Daniel Herschlag lifts the lid on Conflict Finance in the Ukraine war.

https://c4ads.org/commentary/2020-5-26-black-earth/

As the war in Ukraine drags into its 6th year with limited prospect of resolution, its consequences are not limited to the Donbas, or to the Ukrainians trying to survive on both sides of the firing line. Commercial networks profiting from war extend far afield, from neighboring Russia and South Ossetia, to North Korea and Western Europe. This investigation explores how these networks cross national boundaries and contribute to the prolonging of Europe’s deadliest ongoing conflict.

As the war in Ukraine drags into its 6th year with limited prospect of resolution, its consequences are not limited to the Donbas, or to the Ukrainians trying to survive on both sides of the firing line. Commercial networks profiting from war extend far afield, from neighboring Russia and South Ossetia, to North Korea and Western Europe. This investigation explores how these networks cross national boundaries and contribute to the prolonging of Europe’s deadliest ongoing conflict.

At the heart of Russia’s ongoing war with Ukraine is an illicit trade in coal and metal, which customs records indicate was worth more than $286 million in the last three and a half years alone. This illicit market connects suppliers in Ukraine’s occupied territories with buyers around the world, from the UK to Hong Kong, and even to North Korea. To dodge sanctions and obscure the origins of these products, Russian enterprises have used a complex network of firms located in Moscow, Rostov, and self-declared republics like South Ossetia and Abkhazia. As we’ve seen in other illicit systems, similar networks use secrecy jurisdictions and complex webs of companies to hide their activity. Consequently, global supply chains are tainted by their ill-gotten gains.

According to public reporting and C4ADS investigation of Russian customs and corporate records, an important figure behind many of these firms is 34-year-old fugitive Ukrainian oligarch Sergey Kurchenko, referred to in local media as the “coal king of the Donbas.” Russian customs records indicate that the Russian company Gaz Alyans LLC, which the the US Department of the Treasury states is owned or controlled by Kurchenko, is the 9th highest payee by US dollar value of exports of anthracite coal from Russia in between 2016 and May 2019. Given Kurchenko’s alleged role in illicitly transferring coal from Eastern Ukraine into Russia, there is a risk that Gas Alyans coal exports from Russia to other nations may contain illicit coal from Ukraine’s occupied territories.

Using trade records, corporate registry information, and photos and videos captured by Ukrainian researchers, C4ADS worked with the Washington Post to identify the scale of this trade, the primary actors involved, and the potential international consumers of coal and metal products illicitly exported from the Donbas.

A Conflict Economy in Europe

When Russian forces invaded Ukraine’s Donbas region in 2014, the region they seized contained 115 of the 150 coal mines in Ukraine. The Donbas is rich in mineral resources, particularly energy-dense anthracite coal. While Russia and the self-declared states of the Donetsk Peoples Republic (DNR) and Luhansk Peoples Republic (LNR) waged war against Ukraine, actors on both sides of the border found a way to exploit this natural wealth. First reported in 2015, Russian enterprises began exporting large quantities of coal and metal products from the occupied territories into Russia.

Russian enterprises, collaborating with the authorities of the DNR and LNR, have moved 3.2 million metric tons of coal from the occupied territories of Ukraine into Russia between 2016 and 2019 according to Russian import declarations. Some Russian companies importing this coal sell it to domestic consumers in Russia and on international markets. There is a hefty profit to be made — Russian customs records indicate that imports of anthracite coal from Eastern Ukraine have a reported value of roughly $0.04 per kilogram, while Russian export declarations for the same companies involved in buying Donbas coal state that they sell anthracite internationally for around $0.07 per kilogram. If these companies sold all of the anthracite coal sourced from Eastern Ukraine at these rates, they would stand to make potential revenue of more than $96 million dollars.

The US Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) has sanctioned a number of individuals and companies involved in this activity; despite this, sanctioned individuals continue to trade in these products internationally. This trade is reported to sustain the self-declared republics in their ongoing Russian-supported war with Ukraine. Local media reporting indicates that this activity has persisted as recently as April 2020, despite market disruption as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A Question of Scale

Using Russian import declarations, C4ADS found that between January 2016 and May 2019, Russian companies imported $129,142,962.05 worth of coal from the occupied territories of Eastern Ukraine.

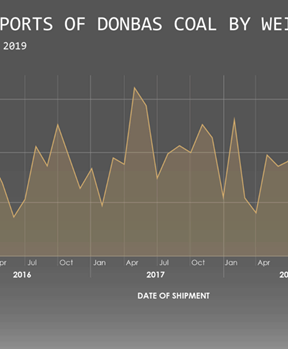

Judging by the same import declarations, Donbas-origin anthracite coal accounts for 97% of imports of anthracite into Russia in this period by dollar value and weight. These imports peaked in 2017, but have continued through 2019 and 2020.

And read on, in the Article.

THE UK RESPONSE

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/conflict-stability-and-security-fund/about

The UK’s latest efforts include:

In 2020-21, CSSF programmes were focused on bringing about changes in the following areas:

· Improving vulnerable groups' resilience to state threats. In Lithuania, the CSSF-funded Strong in Diversity programme brought together young people from Lithuanian and Russian backgrounds, teaching them how to participate in democratic processes, give back to their communities and in turn create meaningful collaboration between ethnic groups in the country. This helped to counter stereotypes created by fake news and populist agendas, and improved social cohesion in the face of divisive narratives.

· Strengthening partner governments' capabilities. Training modules created under the CSSF-funded National Security Communications Team (NSCT) programme enabled the Government of Colombia to deploy a more effective strategic communication response to counter disinformation from hostile state actors.

· UK resilience to state threats. The NSCT launched a campaign to increase awareness of the issue of disinformation amongst the UK population and drive behaviour change. Evaluation of the campaign showed that there has been a positive change of behaviour in the following areas: checking whether an on-line post comes from a trustworthy source, stopping to think if it sounds credible, and fact checking stories before amplifying them.

Is conflict finance a problem which needs more robust response? Or an endemic problem for which there is no reasonable response?