INTERNATIONAL TAX COMPETITIVENESS INDEX

Important research. The 2025 rankings will be an interesting comparison.

International Tax Competitiveness Index 2024

October 21, 2024 By: Alex Mengden

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Introduction

The structure of a country’s tax code is a determining factor of its economic performance. A well-structured tax code is easy for taxpayers to comply with and can promote economic development while raising sufficient revenue for a government’s priorities. In contrast, poorly structured tax systems can be costly, distort economic decision-making, and harm domestic economies.

Many countries have recognized this and have reformed their tax codes. Over the past few decades, marginal tax rates on corporate and individual income have declined significantly across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Now, most OECD nations raise a significant amount of revenue from broad-based taxes such as payroll taxes and value-added taxes (VAT).[1]

Not all recent changes in tax policy among OECD countries have improved the structure of tax systems; some have made a negative impact. Though some countries like the United States, France, and Austria have reduced their corporate income tax rates by several percentage points, others, like Colombia, have increased them. Corporate tax base improvements have occurred in the United Kingdom and Portugal, while the corporate tax base has been made less competitive in Belgium and New Zealand. The United States, Canada, and Finland are phasing out temporary improvements to their corporate tax bases.[2]

The COVID-19 pandemic has led many countries to adopt temporary changes to their tax systems. Faced with revenue shortfalls from the downturn, countries will need to consider how to best structure their tax systems to foster both an economic recovery and raise revenue.

The variety of approaches to taxation among OECD countries creates a need to evaluate these systems relative to each other. For that purpose, we have developed the International Tax Competitiveness Index—a relative comparison of OECD countries’ tax systems with respect to competitiveness and neutrality.

The International Tax Competitiveness Index

The International Tax Competitiveness Index (ITCI) seeks to measure the extent to which a country’s tax system adheres to two important aspects of tax policy: competitiveness and neutrality.

A competitive tax code is one that keeps marginal tax rates low. In today’s globalized world, capital is highly mobile. Businesses can choose to invest in any number of countries throughout the world to find the highest rate of return. This means that businesses will look for countries with lower tax rates on investment to maximize their after-tax rate of return. If a country’s tax rate is too high, it will drive investment elsewhere, leading to slower economic growth. In addition, high marginal tax rates can impede domestic investment and lead to tax avoidance.

According to research from the OECD, corporate taxes are most harmful for economic growth, with personal income taxes and consumption taxes being less harmful. Taxes on immovable property have the smallest impact on growth.[3]

Separately, a neutral tax code is simply one that seeks to raise the most revenue with the fewest economic distortions. This means that it doesn’t favor consumption over saving, as happens with investment taxes and wealth taxes. It also means few or no targeted tax breaks for specific activities carried out by businesses or individuals.

As tax laws become more complex, they also become less neutral. If, in theory, the same taxes apply to all businesses and individuals, but the rules are such that large businesses or wealthy individuals can change their behavior to gain a tax advantage, this undermines the neutrality of a tax system.

A tax code that is competitive and neutral promotes sustainable economic growth and investment while raising sufficient revenue for government priorities.

There are many factors unrelated to taxes which affect a country’s economic performance. Nevertheless, taxes play an important role in the health of a country’s economy.

To measure whether a country’s tax system is neutral and competitive, the ITCI looks at more than 40 tax policy variables. These variables measure not only the level of tax rates, but also how taxes are structured. The Index looks at a country’s corporate taxes, individual income taxes, consumption taxes, property taxes, and the treatment of profits earned overseas. The ITCI gives a comprehensive overview of how developed countries’ tax codes compare, explains why certain tax codes stand out as good or bad models for reform, and provides important insight into how to think about tax policy.

Due to some data limitations, recent tax changes in some countries may not be reflected in this year’s version of the International Tax Competitiveness Index.

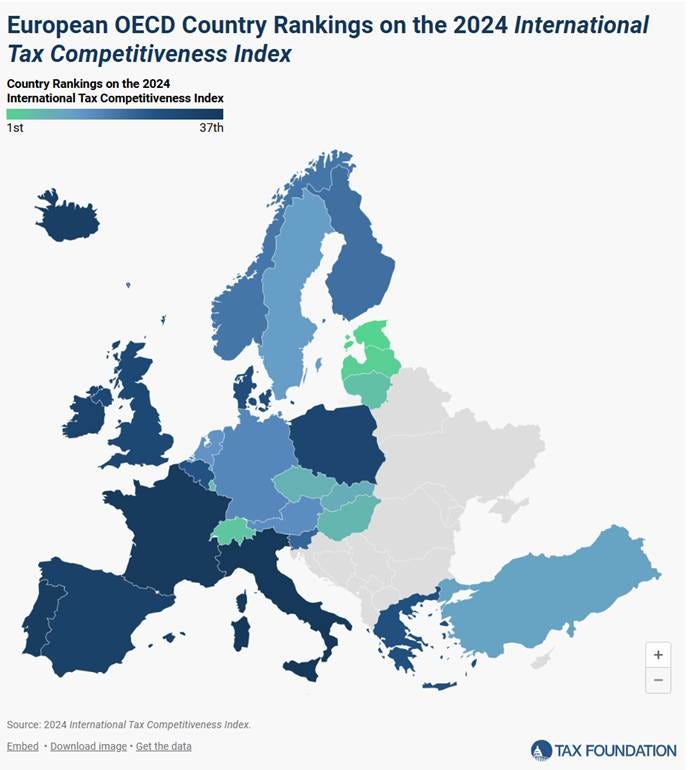

2024 Rankings

For the 11th year in a row, Estonia has the best tax code in the OECD. Its top score is driven by four positive features of its tax system. First, it has a 20 percent tax rate on corporate income that is only applied to distributed profits. Second, it has a flat 20 percent tax on individual income that does not apply to personal dividend income. Third, its property tax applies only to the value of land, rather than to the value of real property or capital. Finally, it has a territorial tax system that exempts 100 percent of foreign profits earned by domestic corporations from domestic taxation, with few restrictions.

While Estonia’s tax system is the most competitive in the OECD, the other top countries’ tax systems receive high scores due to excellence in one or more of the major tax categories.

Latvia, which recently adopted the Estonian system for corporate taxation, also has a relatively efficient system for taxing labor income.

New Zealand has a relatively flat, low-rate individual income tax that also largely exempts capital gains (with a combined top rate of 39 percent), a broad-based VAT, and levies no taxes on inheritance, property transfers, assets, or financial transactions.

Switzerland has a relatively low corporate tax rate (19.7 percent), a low, broad-based consumption tax, and an individual income tax that partially exempts capital gains from taxation.

Lithuania has a low corporate tax rate of 15 percent, allows businesses to deduct a high share of their capital investment costs, and levies a relatively flat and low-rate individual income tax.

Colombia has the least competitive tax system in the OECD. It has a net wealth tax, a financial transaction tax, and the highest corporate income tax rate of 35 percent. Colombia’s VAT covers 41 percent of final consumption, revealing both policy and enforcement gaps.

Italy has the second-least competitive tax system in the OECD. It has multiple distortionary property taxes with separate levies on real estate transfers, estates, and financial transactions, as well as a wealth tax on selected assets. Italy’s relatively high VAT rate of 22 percent applies to the seventh-narrowest consumption tax base in the OECD.

Countries that rank poorly on the ITCI often levy relatively high marginal tax rates on corporate income or have multiple layers of tax rules that contribute to complexity. The five countries at the bottom of the rankings all have higher-than-average combined corporate tax rates. Ireland ranks poorly on the ITCI despite its low corporate tax rate. This is due to high personal income and dividend taxes and a relatively narrow VAT base. The five lowest-ranking countries have unusually high corporate income tax rates, between 25 and 35 percent. Four out of the five lowest-ranking countries have unusually high top income tax thresholds, at 10 to 59 times the average income.

Notable Changes from Last Year

Austria

Austria has been reducing its corporate income tax rate over several years, a process that concluded in 2024. As part of this scheduled reduction, Austria dropped its corporate rate from 25 percent in 2022 to 23 percent in 2024. It also made its accelerated depreciation schedule for buildings permanent. Austria’s rank improved from 17th to 15th.

Canada

In 2024, Canada started to phase out full expensing for machinery and the accelerated investment incentive for buildings and adopted a digital services tax. By increasing its capital gains inclusion rate from half to two-thirds, Canada also hiked its top capital gains rate from 26.7 to 35.8 percent. Canada’s rank fell from 15th to 17th.

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic phased out extraordinary depreciation for machinery and equipment in 2024, reducing the value of its capital allowances by 10 percentage points. It also increased its corporate tax rate from 19 to 21 percent. The Czech Republic’s rank fell from 5th to 8th.

Germany

Germany partially reinstated its accelerated depreciation schedule for machinery and equipment and relaxed its limits on loss carryforwards from 60 to 70 percent of current income for half of the corporate tax base in spring 2024. Germany’s rank improved from 18th to 16th.

Slovenia

Slovenia increased its corporate rate from 19 percent to 22 percent. Slovenia’s rank declined from 16th to 23rd.

United Kingdom

With the 2023 Autumn Statement, the UK made full expensing for plants and equipment and the 50 percent first-year allowance for certain long-life items permanent features of the tax code, averting their expiration by 2026. The UK’s ranking remained 30th.

United States

The US continues to phase out full expensing for plants and equipment. The US increased the relative attractiveness of its cross-border rules, as many other nations started to implement income inclusion rules and domestic top-up taxes within the global minimum tax process. The US rank improved from 23rd to 18th.