LAFFER CURVING

In Modern Monetary Theory, the Laffer Curve is a theory without an object. Taxation merely removes money from circulation, which money the State has placed into circulation, by currency creation. In that model, the only limit on taxation is the capacity of the State to issue new currency.

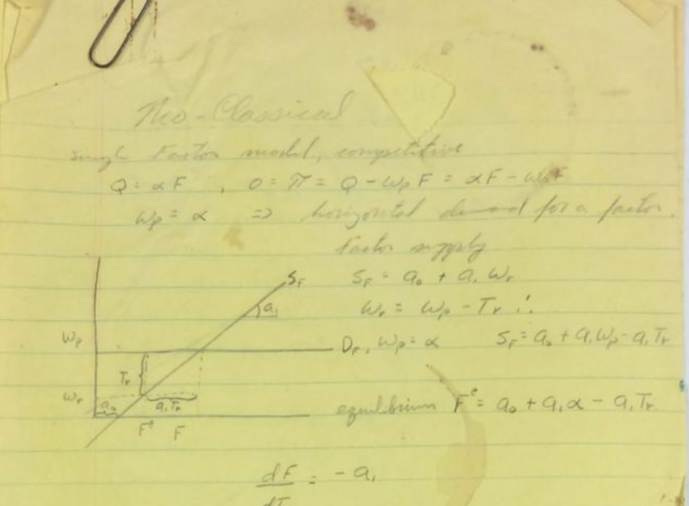

This is a series of documents recently discovered in Arthur Laffer’s archive. The documents include perhaps the original rendering of the Laffer Curve—made prior to or just contemporaneous with the napkin sketch of circa late 1974.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

This series of 32 documents is in the order in which it was discovered in the archive. The first page is of the Laffer curve, derived from the graph an equations above it.

NTR LITERATURE

As Austan Goolsbee wrote in 1999:

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/1999/06/1999b_bpea_goolsbee.pdf

The past decade or so in public finance, however, has seen the birth of a new and important literature very much in the spirit of the Laffer curve, but more sophisticated and potentially much more persuasive. I call it the New Tax Responsiveness (NTR) literature. Perhaps most associated with the work of Lawrence Lindsey and Martin Feldstein but including many others, the NTR literature’s main hypothesis is that high marginal rates have major efficiency costs and fail to raise revenue at the top of the income distribution. In doing this damage, high tax rates need not induce people to work less. Instead, they need only lead people to shift their income out of taxable form. The work of Lindsey, Feldstein, and others has shown that, if people do shift their income in this way, it can imply the same revenue and deadweight loss problems as in the original Laffer curve even if the elasticity of labor supply is zero.

The NTR literature has tried to estimate the impact of this shift with data on high-income people, and it has tended to find large effects. If true, this work means that the marginal deadweight cost of the income tax is quite high, and it calls the progressivity of the tax code into serious question.

IFS authors wrote in 1980:

https://ifs.org.uk/journals/laffer-curve

The tax rate which yields maximum revenue-which we will call the maximum average tax rate- is certainly less than 100 per cent and the corresponding figure for the UK is 36 per cent.

Tax Foundation Europe authors Santiago Calvo López, Diego Sánchez de la Cruz write (September 17, 2024):

Key Findings

- The gap between statutory rates and average effective tax rates for personal income tax (PIT) in the European Union varies significantly, affecting the efficiency and simplicity of the tax system.

- Simplified tax systems, with fewer deductions and exemptions, combined with broader bases help reduce tax avoidance while improving efficiency in revenue collection.

- Those EU Member States with a smaller gap between statutory and average effective tax rates for PIT enjoy higher tax competitiveness, which in turn helps drive investment and economic growth.

- Increasing tax rates without simplifying the system may not always result in a proportional increase in tax revenues, due to changes in incentives and their effect on taxpayer behavior.

- Keeping marginal and average effective tax rates as aligned as possible reduces economic distortions and facilitates tax certainty for companies and individuals, improving the efficiency of the tax system and reducing its negative impact on production.

- EU Member States like Spain and Germany have reached a high tax rate threshold. As a result, additional increases in statutory rates for PIT do not generate a significant increase in tax revenues, a scenario that may be described as a Laffer Curve effect.

The Laffer Curve: A Discussion

As statutory tax rates increase, the implicit tax rates may initially increase proportionally. However, above a certain threshold, implicit rates begin to diverge from statutory rates. This occurs because high tax rates can discourage the generation of additional revenue and encourage tax avoidance, tax evasion, or reduced economic activity. This mechanism is similar to that of the Laffer Curve, which suggests that there is an optimal point of tax rates where tax revenue is maximized. Beyond this point, further increases in statutory tax rates may result in a decrease in revenue due to the contraction of the tax base, reflected in the divergence between statutory and implicit tax rates.

The Laffer Curve is a fundamental concept in economics that illustrates the relationship between taxation levels and tax revenues. Its origin is sometimes dated back to an informal meeting in 1974 in a Washington, DC restaurant, where Arthur B. Laffer, an American economist, explained this theory to a group of journalists and politicians, including Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney. At this meeting, Laffer supposedly illustrated his point on a napkin, which is preserved in the National Museum of American History.

The Laffer Curve shows that as tax rates increase from a low level, tax revenues also increase. However, beyond a certain point, increasing tax rates further reduces tax revenues, due to decreased incentives to work, invest, and produce. This theory suggests that there is an optimal level of taxation that maximizes tax revenues without discouraging economic activity.

Visually, the Laffer Curve is arc-shaped. The horizontal axis represents tax rates, which vary from 0 percent to 100 percent, while the vertical axis represents tax revenues. At the 0 percent tax point, tax revenues are zero. As the tax rate increases, tax revenues also increase until a maximum point is reached. Beyond this point, an increase in the tax rate reduces tax revenues, as individuals and companies find it less attractive to generate taxable income.

The idea behind the Laffer Curve is that there are two tax rates that can generate the same tax revenue: a low rate and a high rate. However, the high rate is detrimental to the economy because it discourages economic activity. Therefore, Laffer argues that reducing tax rates from very high levels can, paradoxically, increase tax revenues. This notion gained prominence during President Ronald Reagan’s administration in the 1980s. The former US leader pursued policies based on Laffer’s theory, significantly reducing tax rates in the hope of stimulating the economy and, in the long run, increasing tax revenues.

Critics of the Laffer Curve argue that its simplicity does not capture the complexity of modern economies and that the effects of changes in tax rates may vary depending on the economic and social context. In addition, they point out that finding the optimal point of the curve is not straightforward and may be different for each economy. Also, practical application of the theory has proven to be difficult in some cases, with results varying considerably in different situations.

The Laffer Curve is also used often to make the case against extremely high tax rates, suggesting that they may be counterproductive and that tax reductions, in certain cases, may be more effective in generating sustainable tax revenues in the long run. This explains why this theoretical insight has become controversial, as supporters of higher taxes will often try to discredit the merits of Laffer’s tool.

In summary, the Laffer Curve is a powerful theoretical tool for understanding the relationship between tax rates and tax revenues, highlighting the importance of finding an optimal balance that maximizes revenue without discouraging economic activity. Its legacy continues to influence fiscal debates and economic policies around the world.

How Far Are We from the Point of Maximum Revenue?

Having reviewed the Laffer Curve, the question of interest is clear: how much can governments raise revenue by increasing statutory tax rates? Indeed, policymakers only have the power to change statutory rates; however, effective rates indicate the ability to raise revenue. Or, to put it another way, how far are we from the peak of the Laffer Curve?

Different academic works have addressed this matter. For example, Holter et al. (2019) investigate how income tax progressivity and household diversity affect the government’s ability to raise taxes, through the modernization of the Laffer Curve.[12] The authors find that the peak of the Laffer Curve in the United States is reached at an average tax rate of 58 percent, which would enable tax revenues to increase by 59 percent if current progressivity is maintained. However, a flat tax system would increase this peak by 7 percent, while a system with Denmark’s progressivity would reduce it by 8 percent. The study shows that higher tax progressivity significantly decreases the labor participation of married women and increases that of single women, especially when their future wages depend on their past work experience. Moreover, high-income households reduce their labor supply more than low-income households when progressivity increases. In conclusion, tax progressivity has a significant impact on the government’s ability to raise revenue. Policies that increase progressivity may have varying effects on revenue and labor participation, depending on household structure and human capital accumulation. This reflects the idea that there is great heterogeneity in the elasticity of the personal income tax.

Mathias Trabandt and Harald Uhlig (2011) analyze Laffer Curves for labor and capital income taxes in the United States, the European Union (EU-14), and different individual European countries, quantifying how tax revenues vary as a function of tax rates.[13] To do so, they estimate the maximal labor tax rate, identifying the point of maximum revenue collection, i.e., the highest level of taxes on labor that an economy can bear before negative effects on workers’ behavior (such as a reduction in hours worked or an increase in tax evasion) cause a decline in total tax revenues.

A key result of the study is that in the European Union, there is significantly less scope for increasing tax revenues by raising tax rates compared to the United States. Specifically, the authors found that in the United States, tax revenue on labor income could increase by 30 percent and on capital income by 6 percent by maximizing tax rates. In contrast, for the EU-14, these increases are much smaller, with a potential increase of 8 percent for labor taxes and only 1 percent for capital taxes. This result suggests that the EU-14 countries are already closer to the downward slope of their respective Laffer Curves, thus limiting their ability to significantly increase tax revenues through higher tax rates.

The concept of “self-financing percentage” is central to understanding these results. This percentage refers to the proportion of a tax cut that is “self-financing” through incentive effects that increase economic activity and thus the tax base. For example, if a country reduces the tax rate on labor income, part of the initial loss of tax revenue may be recovered due to an increase in labor supply and, consequently, in taxable labor income. In the study, it is estimated that in the EU-14, 54 percent of a labor tax cut and 79 percent of a capital tax cut are self-financing. This means that more than half of the tax revenue lost from labor tax cuts and almost four-fifths of the tax revenue lost from capital tax cuts is recovered through the increased economic activity induced by lower taxes. Therefore, although tax cuts do not entirely “pay for themselves,” their actual budgetary impact is significantly lower than that suggested by static assessments.

WEALTH TAXES

The recent experience of the UK provides a laboratory study for Laffer Curve economics.

In 2025, the British finance minister removed tax breaks for so called “non-domiciled”. The result was a flight of capital rich individuals. Other taxes were also pushed up, in a fiscal tightening which was one of the highest in post-ear record in that country.

The revenue raising impact from each category of tax increase has failed to meet government forecasts.

The lesson already drawn from Laffer Economics by the UK State appears to be that a wealth tax is pointless. The behavioral adjustments of the class of persons targeted by the tax would render the tax ineffective.

A MAP IN HINDSIGHT

Laffer Economics may be reduced to the tautology that a state cannot collect more tax than it is able to raise effectively. In a broad sense, this truism was known to medieval monarchs.

Insofar as it is a valuable insight, there is little useful basis for forecasting. Dynamic modeling in any open system with multivarious factors, amounts to little better than a mere guess. More useful is post facto modeling, using the Laffer insight as a compass.

But there is a critical difference between the inutility of Laffer Economics as a quant model, and a conclusion that the Laffer effect does not exist. Laffer effects are being seen in real time in the failing efforts of the British treasury to ramp up taxation on an already high base.

Suppose that economic theory supported by quantized models dictated that a particular tax rise would not result in increased tax collection – would a State do it anyway?