TWO MODELS OF TAX PSYCHOLOGY

Psychology has devoted substantial research into the reasons why people do pay tax, and even more to why people don’t: and what psychological techniques tax authorities can use to alter behaviour.

The Cambridge Handbook of Psychology and Economic Behaviour includes Chapters 13 and 14 which consider:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

· Tax psychology

· New ways of understanding tax compliance.

Chapter 13 sets out 2 Models:

13.2.1 Rational Choice Model

The first economic analysis of tax compliance behavior can be traced back to the pioneering work of Allingham and Sandmo (1972). Their analytic model is a straightforward application of Becker’s (1968) economics-of-crime paradigm to individual income tax. Taxpayers are assumed to be motivated only to maximize their expected utility from financial outcomes by trading off the potential costs of evasion against the costs of compliance. In this framework, a taxpayer’s evasion decision is analogous to portfolio choice between the certain tax position (honest reporting) and the risky prospect of evasion (Sandmo, 2005); the taxpayer is deemed a gambler playing with the tax authority under the risk of being detected. The Allingham and Sandmo (1972) model is often called the standard economic model of tax evasion. In this approach, the key policy parameters affecting tax evasion are the tax rate, the detection probability, and the penalty imposed on evasion. The central point is that an individual pays taxes because of the fear of detection and punishment. Thus, this approach is referred to as the economic deterrence paradigm.

The standard economic model predicts that tax evasion decreases as the economic deterrence factors increase, that is, tax rate, probability of being detected, and penalty rate. These predictions have been extensively examined empirically (Kirchler et al., 2010). First, the size of the relationships between these factors and compliance has proven to be mixed in laboratory experiments. Second, given actual low rates of audits and rather mild penalties in the real world, a taxpayer’s rational choice should be to evade most of his or her taxable income, yet it is observed in many countries that the aggregate level of compliance is far higher than would be predicted by the standard economic model (Alm, McClelland, and Schulze, 1992). Lastly, field experiments have revealed that deterrence effects can have mixed results. For instance, in a randomized field experiment manipulating deterrence by threat-of-audit letters, Slemrod, Blumenthal, and Christian (2001) confirmed increased compliance in the group of middle- and low-income taxpayers, but observed adverse responses among high-income taxpayers; high-income taxpayers receiving an audit threat reported lower income than the control group. Kleven et al. (2011) showed that the threat-of-audit letters had significant effects on self-reported income but no effect on third-party reported income.

A model should be evaluated in terms of reasonableness of its assumptions, its predictive power, and its potential usefulness for policy makers. First, the standard economic model assumes that individuals are perfectly rational, selfish, isolated utility maximizers. The underlying assumptions have been criticized by both behavioral economists and psychologists for their lack of reality and humanity (Cullis and Lewis, 1997). Second, neoclassical economists tend to believe that assumptions do not matter as long as the predictions are correct.

However, the standard model has failed to explain relatively high levels of actual compliance (Bordignon, 1993). Lastly, the deterrence framework implies enforcement strategy is the only thing that matters to deter the taxpayer from evading. Tax policy based on these assumptions is likely to be inefficient, making it necessary for the tax administration to spend a huge amount of resources monitoring and punishing people.

13.2.2 Behavioral Choice Model

Behavioral choice models deal with the cognitive and contextual aspects in the taxpayer’s decision process. It is too burdensome a task for ordinary taxpayers to calculate an optimal concealment of taxable income. Having limited cognitive power, they are susceptible to the ways in which a problem is “framed,” and often their judgments and choices are different from those predicted by the standard economic model. For example, whether a tax issue is framed as a bonus for those with children or a penalty for the childless can affect a taxpayer’s attitude toward the tax policy even though the economic consequences are the same (McCaffery and Baron, 2004).

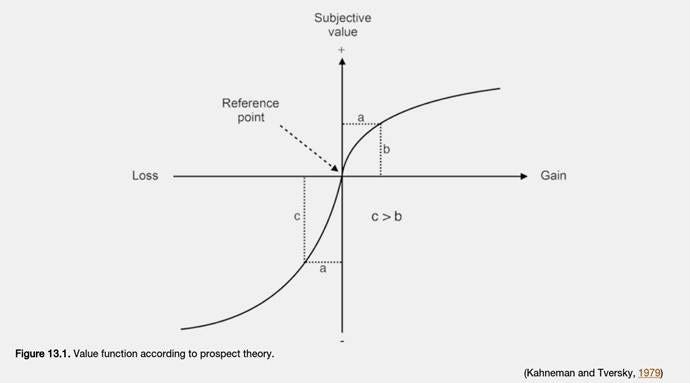

Contrary to the expected utility theory, prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979) postulates that an individual’s decision outcomes are evaluated by changes in income from some reference point, not by the final state of his or her wealth.

The subjective value (Figure 13.1) of gains or losses is determined by a value function that is steeper for losses than for gains, concave for gains, but convex for losses. This implies that the subjective value of a given loss is perceived as more negative than the positive effect of a gain of the same size. As a consequence, people generally try to avoid losses. Depending on whether a potential outcome constitutes a loss or a gain from a person’s reference point can thus affect the willingness to take risks; people are risk averse with regards to gains but risk seeking in the domain of losses.

Prospect theory provides a framework to understand facets of individual tax behavior that cannot be accounted for by the standard economic model, as for instance framing effects, withholding phenomena, effects of prior audits on subsequent compliance, income nonfungibility, and mental accounting practices.

For instance, taxpayers facing a balance due, generally framed as a loss, tend to be risk seeking, making them more likely to evade (Chang, Nichols, and Schultz, 1987; Kirchler and Maciejovsky, 2001). On the other hand, taxpayers claiming a refund, generally framed as a gain, tend to be risk averse, making them more likely to comply (Elffers and Hessing, 1997; Kirchler and Maciejovsky, 2001; Yaniv, 1999). The effect of advance tax payment (withholding status) on tax compliance is referred to as the “withholding phenomenon” (Schepanski and Shearer, 1995).

Boylan and Sprinkle (2001) have provided insight into the relation between tax rates and taxpayer compliance by distinguishing endowed income from earned income: when income was endowed, participants responded to tax rate increases by reporting less income, whereas they reported more income for earned income. Kirchler et al. (2009) have confirmed the effect of income source by showing that tax evasion was more pronounced in low-effort conditions. They noted that effort changed the aspiration level (reference point) rather than the slope of the value function, and made high-effort income earners more risk averse and more compliant.

Tax audits constitute not only a reaction to past tax noncompliance, but their consequences represent a cause for future behaviors (Maciejovsky, Kirchler, and Schwarzenberger, 2007). As soldiers would take shelter in bomb craters in the belief that it is unlikely for bombs to fall in the same place twice (which Mittone, 2006, refers to as the “bomb crater effect”), taxpayers may believe that it is safer to evade taxes right after a tax audit has taken place. The effect may be attributable to the misperception of chance, or alternatively taxpayers may attempt to repair their “losses” incurred during the previous audit by engaging in evasion in subsequent tax filings (Andreoni, Erard, and Feinstein, 1998). However there is some support for a contrary “echo effect,” where audits, experienced in early stages of taxpaying life cycle, may lead to an increase in compliance (Kastlunger et al., 2009). Experimental evidence suggests that increasing the time lag between tax filing and feedback on audits enhances compliance, mainly due to overweighting of subjective audit probabilities (Kogler, Mittone, and Kirchler, 2015). Field data from the United States (Beer et al., 2015) shows that audits do not affect all taxpayers in the same way. An analysis of Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data by Beer et al. (2015) has revealed that audits increase reported income of sole proprietors substantially if they had additional taxes assessed. Those taxpayers, however, whose audits did not result in an additional tax assessment reported less income in subsequent years. Furthermore, Mendoza, Wielhouver, and Kirchler (2015) have investigated the impact of auditing levels on tax evasion in a comparison of forty-seven countries and found a U-shaped relationship. This means that audits affect compliance positively until a certain auditing level is reached. Thus, simply increasing audits to increase compliance levels is not necessarily the most optimal policy strategy.

Mental accounting describes the set of individuals’ cognitive operations to organize, evaluate, and keep track of financial activities (Thaler, 1999). Generally, people have various mental accounts, for instance to pay for their rent, food, or leisure activities. Drawing on this theory in the context of taxes, taxpayers might designate a separate mental account for taxes due in the future. In this case, tax payments would not be mentally deducted from personal income, but from a designated separate account, making it less likely that paying one’s taxes will be perceived as a loss. Muehlbacher, Hartl, and Kirchler (2015) have shown that the mental segregation of taxes due from net income affects a taxpayer’s reference point in the compliance decision and results in higher tax compliance. However, the effect seems not only to be driven by a shift in reference point to the net income, but because it prevents taxpayers from overspending funds that are needed to pay taxes due later on in the business year. Thus, mental accounting could be regarded as a technique to improve the representation of tax liability without perceiving them as a loss.

…

13.4 The Interaction Between Taxpayers and Tax Authorities

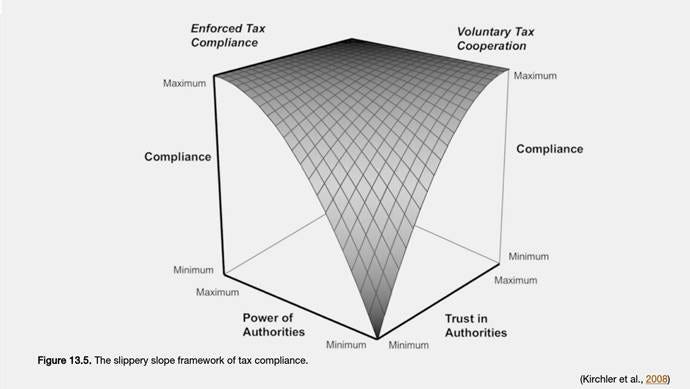

Kirchler, Hoelzl, and Wahl (2008) integrated economic and sociopsychological factors into one comprehensive framework with two dimensions: trust in authorities and power of authorities.

The slippery slope framework (SSF), depicted in Figure 13.5, postulates that power and trust determine tax compliance.

- Power is defined as the capacity of tax authorities to apply deterrence measures.

- Trust, on the other hand, stems from fairness perceptions, prevalent norms, attitudes, and provided services for taxpayers.

On the aggregate level, these two dimensions define the climate between tax authorities and taxpayers.

When tax authorities are primarily perceived as powerful, the SSF postulates an antagonistic climate between taxpayers and authorities. If, however, tax authorities are experienced as trustworthy, a synergistic climate is prevalent, where tax authorities are perceived as benevolent.

On the individual taxpayer level, these interaction climates lead to different motivations to comply with tax law: in an antagonistic climate, taxpayers are presumably compliant with the law because of the fear of detection and fines (enforced compliance); while in a synergistic climate compliance derives from the mindset to contribute to the community (voluntary cooperation).

In the case of enforced compliance, legal coercion may be effective, whereas in the case of voluntary cooperation, social representations of taxes, including subjective tax knowledge, attitudes, norms, and fairness, come into play.

The underlying assumptions of the SSF have been confirmed empirically in a number of countries with differing cultural and economic settings (Kastlunger et al., 2013; Kogler et al., 2013; Muehlbacher, Kirchler, and Schwarzenberger, 2011). The largest study was conducted in a total of forty-four countries from five continents (Kogler et al., 2014). Participants were randomly assigned to one of four different scenarios describing a fictitious country with either high or low trust and power.

Tax compliance intentions were highest in scenarios where authorities were described as trustworthy and powerful, while intended compliance was lowest in the condition characterized by low trust and low power.

On a country level, the results confirmed that trust positively influenced tax compliance intentions in all investigated countries. The effect of power was found for forty-three out of forty-four countries.

The SFF does not only provide a conceptual framework to understand tax compliance research, but also serves as an operational policy tool to devise regulatory strategies. According to the SSF, tax compliance can be achieved either by increasing power or by building trustworthy relationships.

Tax authorities’ orientation toward taxpayers and their interaction style create a tax climate: a “cops and robbers” approach stimulates an antagonistic climate in which and taxpayers seek their self-interest, whereas a “service and client” approach stimulates a climate of trust and cooperation.

By implementing measures that increase trust in authorities, tax authorities should be perceived as transparent and capable of handling taxpayers’ needs. If deterrence is not used arbitrarily but targeted at high-risk groups, power of the authorities should be perceived as justified and as a protection mechanism against free riders.

…

The deterrence model relies heavily on audit probability and penalties as motivators of compliance and neglects the psychological and social aspects of taxation and the interaction dynamics of actors in the field. Taxpayers would feel that they are not trusted as moral agents and refuse to act in moral ways if the tax authority regards all taxpayers as potential criminals. As Cullis and Lewis (1997, p. 310) noted,

“If we believe taxpayers are selfish utility maximizers, taxpayers will behave like selfish utility maximizers. If we believe taxpayers have a moral nature, a sense of obligation or civic duty, taxpayers will reveal this side of their nature.”

Moreover, control and punishment may elicit unintended side effects that crowd out taxpayers’ willingness to paying taxes if it is not justly practiced (Feld and Frey, 2002). In short, deterrence may be a necessary condition, but not the sufficient condition for all taxpayer compliance.

While the standard economic approaches stress the relevance of external variables such as tax rate, income, probability of audits, and severity of fines, fiscal psychology has shown the importance of sociopsychological variables that shape higher tax morale and lead to voluntary cooperation. In the tax compliance literature, there was a significant two-step paradigm shift from the exclusive focus on economic factors toward individual psychological and sociopsychological factors (Alm et al., 2012). The SSF reconciles different research paradigms by assigning economic as well as psychological factors to two dimensions: power of authority and trust in authority. In the SSF, the dynamic of power and trust, the tax climate, determines different paths to compliance: enforced or voluntary compliance. The SSF provides an insightful way to apprehend puzzling empirical findings from economic psychological studies of tax behavior.

Concerning practical applications, behavioral nudges may help to construct more efficient tax policies that reduce enforcement costs. For example, Shu et al. (2012) have reported that signing honor codes and tax self-reports before filing taxes triggered more compliant behavior. Or governments could change taxpayers’ perceptions of exchange equity simply via information campaigns (Holler et al., 2008).

In practice, the Behavioural Insights Team in the United Kingdom and the “I Nudge You” Team in Denmark incorporated the findings of behavioral economics and economic psychology into policies that aim to improve tax compliance. Furthermore, acknowledging the importance of collaborating with tax scholars, tax administrations can provide opportunities for conducting large-scale field experiments in order to develop cost-effective strategies to foster tax compliance with reference to scientific knowledge (e.g., Hallsworth et al., 2014).

The last decade has witnessed the change of research paradigms on tax behavior and regulatory practice in line with the propositions of the SSF (Kirchler, Kogler, and Muehlbacher, 2014). Many countries recognize cooperative compliance as an effective means of achieving tax compliance and establish close relationships between tax authorities and taxpayers that encourage mutual trust in tax matters (OECD, 2013). In 2005, the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration introduced “horizontal monitoring,” as an alternative to the traditional “vertical monitoring.” Horizontal monitoring allows large companies to enter a partnership with the tax authority, where both work closely together and meet regularly with the key objective of timely and legally accurate tax collections. The advantage for the companies is given by the fact that they have no uncertainty about their tax liabilities and do not have to expect additional tax payments for a concluded accounting period. Thus, companies’ compliance costs are reduced and they can benefit from legal security. The partnership is also beneficial for the tax authority because personnel can be shifted to other risk areas (OECD, 2015). Other examples of such programs include the US Compliance Assurance Process, which has existed since 2005; Australia’s Annual Compliance Arrangement, which started in 2008; and the South Korean Horizontal Compliance Program, which was established in 2010 (De Simone, Sansing, and Seidman, 2013).

In conclusion, the SSF recognizes the necessity of enforcement, but also stresses the role of tax authorities as service providers for taxpayers based upon trustworthy relationships (Alm et al., 2012). Thus, it is crucial to view tax evasion from different perspectives in order to foster high levels of compliance.

The 2 models divide between utility calculation and social appreciation. Both operate under political dynamics. There seems to be an implicit denial of this reality running through both models.